You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Ancient monuments’ category.

Helland is situated around three-quarters of a mile South of Mabe in Cornwall.

Standing on the wall at the edge of the garden of Helland House and overlooking the minor Brill to Lamanva road, a little granite wheel-headed wayside cross is found.

The settlement at Helland was first recorded during 1323 as ‘Hellan’ although it was certainly a place of human occupation for countless years before that.

Helland is a Cornish place name derived from the Cornish language ‘hen’ and ‘lann’ so translates into English as ‘old cemetery’ or ‘old religious enclosure’.

Lanns are common in Cornwall and indeed Wales and date from the early Christian period between the 5th and 7th centuries. These were settlements which comprised an enclosure surrounding a consecrated area. Domestic habitations, a chapel and indeed a cemetery were often found in lanns and a large number of churches were later constructed on such sites.

Again, an examination of toponymy reveals much for a lann did indeed exist at Helland and the site is marked as a graveyard on the 1908 Ordnance Survey map.

The great antiquarian, Arthur G. Langdon writing in his ‘Old Cornish Crosses’ published in 1896, informed of the garden at Helland House as once being the site of an ancient chapel and graveyard. It appears that he had a discussion with a local farmer, a William Rail, who related carrying out work in the garden and uncovering the cross, an old font bowl and a quantity of old roofing slates which he suspected belonged to the lost buildings. It was Mr. Rail who erected the cross on its present site

Writing of the site in 1925 and again in 1930, the Cornish historian and antiquarian Charles Henderson (b.1900 d.1933) recorded the existence of an Early Mediaeval (410 to 1065) chapel and burials of a so-called ‘primitive’ nature with a rather charming local tradition of children visiting the chapel each Spring time, bringing flowers.

The cross as seen now stands at around three feet eight inches in height with the head measuring around one foot ten inches in diameter. The cross shaft tapers out slightly from 13 inches at its neck to 16 inches at its base. The monument is between nine and ten inches in thickness.

In terms of decoration, there is an incised Saint Andrew’s cross enclosed by a double bead on the outward face and this bead extends down the shaft where a rectangle has been carved with diagonal lines running from corner to corner. Just below the head and on the upper part of the neck bosses have been carved. The reverse side has been carved with an incised equal limbed cross with shallow holes at the ends enclosed by an incised ring which extends down the shaft.

Charles Henderson proposed that the cross was pre-Norman in date but in ‘Ancient and High Crosses of Cornwall’, the authors Ann Preston-Jones, Andrew Langdon and Elisabeth Okasha suggest it dates from post-Norman Conquest date probably of the 12th or 13th centuries.

Both the cross and the wall upon which it stands are now Scheduled Monuments.

References

- Placenames in Cornwall and Scilly – Craig Weatherhill, Wessex Books in association with Westcountry Books, Launceston, Cornwall 2005

- A Guide to Cornish Place-Names – R. Morton Nance, The Federation of Old Cornwall Societies 1956

- Mabe Church and Parish – Charles Henderson, the King’s Stone Press, 1930

- The Cornish Church Guide and Parochial History of Cornwall – Charles Henderson, D.Bradford Barton 1964

- Stone Crosses in West Cornwall – Andrew Langdon, Federation of Old Cornwall Societies, Cornwall 1999

- Ancient and High Crosses of Cornwall – Ann Preston-Jones. Andrew Langdon and Elisabeth Okasha, University of Exeter Press, 2021

- Old Cornish Crosses – Arthur G. Langdon, John Romilly Allen, Joseph Pollard Pub. of Truro, Cornwall, 1896 (available on the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/oldcornishcrosse00lang/mode/2up)

All images author’s own, except where stated.

See similar articles by Myghal Map Serpren

By Myghal Map Serpren

This menhir of locally sourced granite standing to a height of just under eight feet has had something of a chequered and indeed controversial recent history. It can be found on farmland set on the South Eastern side of the B3291 road at Eathorne Farm in the Parish of Mabe in Cornwall.

The name ‘Eathorne’ merits toponymical consideration. Even the recognised expert in this field, the late Craig Weatherhill found the name baffling and his research established that it was recorded as ‘Eytron’ in 1392 and later ‘Ethron’ in 1417. He suggested that the second syllable notably ‘thorne’ may derive from the Cornish language ‘tron’ meaning a ‘nose’ or ‘hillspur’.

Described by many as “slim and regular in shape with a curiously bent top” – a comment originally made by the late Craig Weatherhill in his book ‘Cornovia – Ancient Sites of Cornwall and Scilly’, current thinking indicates that this menhir was first erected in the Bronze Age (2500BCE to 801BCE), possibly fell or was moved and later re-erected during the Roman or post Roman period (43CE to 409CE).

A very public outcry resulted following no less than three accounts of a recent occurrence regarding the menhir:

- One informs that in June 1991, the landowning farmer determined the stone to be ‘an obstruction to the plough’ and removed it to behind a barn in the farmyard.

- A second account records that the stone was removed by the farmer in 1992 as he felt it a pagan artefact and an offence to his Christian beliefs.

- A third report has it that the same farmer removed the stone because ‘he felt uneasy about it’.

Whatever the actual facts are, doubtless somewhere between all three accounts, as a result of protest, the Eathorne Menhir was re-erected on 3rd October 1992, during ‘Archaeology Alive Week’ by members of the Cornwall Archaeological Unit, the Cornwall Archaeological Society and staff of Tehidy Country Park.

The Cornwall Archaeological Review of 1992 to 1993 recorded “the stone, which had been taken down by the farmer, is now near but not in, its original position”.

It appears that it had been placed close to a hedge so allowing it to become lost in vegetation and covered in fencing wire and that it had incurred damage as a result of the various moves.

By 2005, Eathorne Farm had undergone a change of ownership and the incoming farmer indicated support for the menhir being restored to its rightful spot.

Aerial photographs obtained in 1946 by the Royal Air Force and later in 1989 by Cornwall Council firmly identified its original position, so on 14th August, 2005, an eclectic team from the Historic Environment Service of Cornwall Council, the Cornwall Archaeological Society and the Cornwall Earth Mysteries Group undertook the work.

A mechanical digger was employed to remove the topsoil which revealed the original site, and during this operation, six flints, a number of pebbles and also notably charcoal was uncovered the latter of which was carefully retained to allow for radiocarbon dating.

The menhir was then re-erected in the correct position.

The subsequent radiocarbon procedure revealed the charcoal to have been oak and in the date range 120CE to 220CE with a 56% probability or 70CE to 240CE with a 95% probability. The results of this process has been used to date the menhir as previously discussed.

Said by some to be standing at a ‘sacred energy point’, the Eathorne Menhir does not appear to enjoy any form of scheduling or legal protection and whether there is some esoteric significance or not, it is of great historic and archaeological interest and one can but hope that the monument remains secure having finally returned to its original site.

References

- Placenames in Cornwall and Scilly – Craig Weatherhill, Wessex Books in association with Westcountry Books, Launceston, Cornwall 2005

- The Eathorne Menhir – paper by Andy M. Jones, Principal Archaeologist, Cornwall Archaeological Unit, Cornwall Council, 2006 in collaboration with Steve Hartgroves, Graeme Kirkham and Rowena Gale and Anna Lawson-Jones to which a link here: https://www.academia.edu/6605488/The_Eathorne_Menhir

- Cornovia, Ancient Sites of Cornwall & Scilly 4000 BC – 1000 AD – Craig Weatherhill, Halsgrove, 2011

All images author’s own, except where stated.

See similar articles by Myghal Map Serpren

By Myghal Map Serpren

The Parish, Village And Toponymy

Sithney is a village and parish in West Cornwall between Marazion and Helston and is one of several other hamlets and villages in the parish notably St Johns, Penrose, Mellangoose, Lower Prospidnick, Dowga, Sithney Common, Sithney Green, Coverack, Crown Town also known as Gudna, Lowertown, Chyreen and Lower Tregadjack.

Writing in his ‘Wendron and Sithney in 18th Century’ published in 1930, the Reverend Canon Gilbert Hunter Doble MA (b.1880 d.1945), who in addition to being a clergyman was a historical writer and researcher of some note, suggested that Sithney once had an Iron Age or Romano British Round (800BCE to 400CE) situated near to the site of the present church. He based this finding on a field there having the name ‘Parc an Gear’ translating from the Cornish as ‘Field of the Fort’. Such field names are common in Cornwall and frequently can indicate what originally existed in the location. No trace of the structure remains but it does tend to suggest that what is now known as Sithney has a long history of human habitation.

Sithney was recorded as ‘Merthersythny’ in 1320 from the Cornish language ‘merther Sydhny’ meaning ‘St Sythni’s grave or reliquary’.

By 1623, the presence of the church saw the placename ‘Egloseynncy’ in use derived from the Cornish language ‘eglos Sydhney’ translating into English as ‘St Sythni’s church’.

Some sources refer to the settlement at Sithney being possibly first recorded in 1140 as ‘Merdreseni’. Care should be taken though, as this doubtless refers to the fair of Merthersythney, which since the 13th century is held on 5th August annually at Goldsithney some seven miles distant, with the name ‘Goldsithney’ actually translating from Cornish ‘gol Sithney’ into English as ‘Sithney Fair’.

The Legend Of Saint Sithney

Sithney, known as ‘Sidinius’ in Latin and ‘Sezni’ ‘Sezny’ and ‘Sezin’ in Breton, is believed to have been one of the multitude of Christian missionaries from Ireland who arrived in Cornwall during the 5th and 6th centuries bringing news of the Gospel.

He was active during the period 410 to 449, commonly referred to as the ‘sub-Roman’ era which saw the departure of the Roman Empire from Britain. In addition to Cornwall, he also had a presence in Brittany where it is said he went and where he is venerated at Guissény formerly Ploesezny and elsewhere.

One of many legends relating to Saint Sithney is an adaption of another which concerns Saint Kieran of Saighir, a monastic site in Clareen, County Offaly, Ireland.

Kieran or Ciarán is one of the twelve Apostles of Ireland and research indicates that he also undertook the journey to Cornwall in the 5th century where he became known as Saint Piran, the Patron Saint of Tinners and now widely regarded as the Patron Saint of all Cornwall.

Writing in Breton during 1636, Albert Le Grand (b.1599 d.1631), a Dominican brother at Rennes Monastery recorded the lives of 78 saints based on his research of early documents and his studies included Sithney.

His original work on Sithney was published separately in 1848 and entitled ‘Buez Sant Sezny’.

This informed of Sithney’s arrival at what is now Guic-Sezni in Brittany from Cornwall during the early Christian period and of how he founded the monastery there.

It was said that God requested that Sithney act as patron saint for young maidens who were seeking a husband.

Whilst showing humility, Sithney declined informing God that he would much prefer to care for mad dogs than for young women.

And so it was to be and the saint’s Holy Well provided water to dogs which were sick or mad and Sithney remains the patron saint who is called on to cure dogs of rabies, of the resultant hydrophobia and of madness, as well as having the patronage of Sithney in Cornwall.

His canonisation occurred before the adoption of formal processes and so he became a saint more by custom owing to his virtuous and holy life.

Sithney is believed to have died during 629 and is variously referred to as a Monk, Confessor, Abbott and Bishop and his feast day occurs on the 4th August in the village which now bears his name, on the 6th March in Guisseny, Brittany, and 19th September to avoid celebration during the Lent.

The Monastery of Guic-Sezni in Brittany now claims to have custody of Sithney’s relics said to include one of his arms. Writing in 1478, the chronicler William Worcester, also known as William of Worcester, William Worcestre or William Botoner (b.1415 d. c.1482), informed that his body laid within the church in Sithney where a long-held tradition has it that he is interred beneath the North Transept.

The Parish Church Of Saint Sithney

Of the early Celtic holy site at Sithney, nothing remains.

Current ecclesiastical records show that in a later period, during 1230, the church belonged to Roger de Antrenon and Nicola his wife, after whom Antron at Mabe near Penryn is named, who attached to it a charge of four shillings per annum to the priory of Saint Germans.

By 1267 it was appropriated to Glasney College at Penryn, the last rector ceded his benefice to the college in 1270 and the Bishop appointed the first vicar, Alan de Hellestone who is thought to have come from Saint John the Baptist’s Hospital which had been established during the early 13th century near Helston.

The Church of Saint Sithney seen today is mainly of granite and dates mostly from the 15th century with some exceptions and can broadly be described as being in the Pointed Style of architecture.

The church was consecrated in 1497 and stands on the foundations of an earlier Norman building.

The building consists of a chancel with North and South aisles, a nave of four bays, a shallow North transept below which it is said Saint Sithney was interred, a South transept, a porch to the South with the porch on the North used as a vestry and priest’s door. The East end of the chancel probably dates from the earlier church building. The windows are mainly Perpendicular in style.

The three-stage embattled tower with pinnacles stands to an overall height of 67 feet and contains three bells cast in 1771 and recast in 1950.

The South East pinnacle has a carved statue of Saint Sithney which faces in the direction of Brittany where he had very strong links with some sources informing that he came from earlier rather than Ireland.

At Guisseny in Brittany, a carved wooden statue of Saint Sithney stands above the door of the church earlier bearing his name and looks across the waters to Saint Sithney in Cornwall.

A copy of the statue of Saint Sithney stands in his church in Cornwall. This work was carried out by Rene Bagout, a Breton wood carver and presented to the church during Easter, 1986 by seven priests from Brittany who were visiting Sithney.

Every year, the statues in both churches are crowned with a garland of flowers on the feast day.

A carved depiction of the head of King Henry VII (b.1457 d.1509) who reigned from 1485 until his death in 1509 adorns the South West pinnacle.

The church was almost wholly re-roofed during the latter part of the 19th century, the interior was replastered and the original 15th-century roof and many of the original fittings were removed. Recent restoration work in 2018 revealed the skeletons of many parishioners interred beneath the church floor.

The South porch dates from the Elizabethan period and houses a stoup, a granite basin for the storage of Holy Water. Careful examination also reveals ornamented stones dating from the earlier Norman church incorporated into the porch wall with other such original stones being visible inside the church building.

The church flooring is of note although comprising Victorian quarry tiles in the main, Mediaeval floor tiles are in place near the altar and these were made at the now-lost Glasney College at Penryn.

The window in the Baptistry incorporates stained glass roundels dating from the 13th or 14th century. By chance, they survived the destruction wreaked on churches during the Cromwellian period and were mounted in the windows in 1851. Initially, this window was situated behind the organ but work carried out in 1925 saw the window moved to its current site and the stained glass is again visible.

A wooden pew end dating from 1480 has been fixed to the Baptistry wall.

On the North wall of the Lady Chapel are rood stairs which originally led to the gallery above a rood screen.

A large four-framed panel is suspended from the roof of the North aisle, painted with a copy of a letter of thanks written by King Charles I (b. 1600 d.1649) and addressed to the people of Cornwall for the support they gave him during the Civil War and written by him during 1642 whilst he was at Sudeley Castle, Gloucestershire. The beautiful work was carried out by local men Henry Arundell and Samuel James.

The Font

The font in the Parish Church of Saint Sithney has a bowl dating from the Norman period, specifically 1080 to 1100. It was carved from Greenstone, a form of volcanic rock found in Cornwall. It has an outside diameter of approximately 19 inches, an inside diameter of around 14 inches and stands just short of 13 inches in height. It is decorated with a chevron-carved rim and cable moulding under the font and stands on a granite pedestal dating from around 1750.

The font was discovered during the works of 1853 beneath the Sanctuary where it had been employed to support the floor, and was immediately passed to the church being constructed at Carnmenellis which was being constructed because of the burgeoning population there brought about by mining.

The church at Carnmenellis fell into disuse following the decline in mining, and the font was restored to Saint Sithney’s church in 1922.

The Coffin Slab

Now found on the North wall and directly facing the South door, a granite slab which served as a coffin lid dates from the 13th century or indeed far earlier.

In 1918 this was situated in a boundary wall at the base of Saint John’s Hill, Helston close to the site of the former Mediaeval Saint John’s Priory and hospital and the then landowner, the Duke of Leeds gave consent for the artefact to be moved to the church.

Standing around five feet seven inches high, it is thought that the stone was the lid of the sarcophagus of Prior Penhalurick and that it may actually date from the 9th century.

With its extended and flared carved Latin cross and bearing in mind the hospital which then existed at the priory, the lid appears very Templar-like indeed.

With the dissolution of the monasteries during the 16th century, the priory and hospital at Saint John’s were vandalised and by 1545, lay in ruins.

The ‘Wheal Fortune’ Mediaeval Cross

Now found in the churchyard at Saint Sithney Parish Church, this wheel headed cross head of granite later mounted on a pillar dates from the Mediaeval period (1066 to 1539) and was rediscovered during the 1940s at Wheal Fortune Farm, Carnmeal Downs, situated in the nearby Breage Parish.

The head measures one foot five inches in diameter and is seven inches in thickness. Mounted on an inscribed granite pillar during 1977, it stands to an overall height of around five feet eight inches.

One face of the artefact bears an equal limbed cross with a small depression near the centre but the reverse face was completely hollowed out to a depth of just over four inches to allow for it to be used as an agricultural feeding bowl. This terrible act of vandalism has occurred with crosses elsewhere.

Having been purchased on discovery for two shillings and sixpence, it spent a time in the Royal Cornwall Museum in Truro before being moved to the churchyard at Saint Sithney’s and mounted on a pre-existing modern pillar bearing the inscription ‘Unveiled by John Williams on his Ninetieth Birthday 12.11.1972 A.M.D.G.’ (A.M.D.G. not A.M.D.C. as cited in some references; Latin: ‘Ad maiorem Dei gloriam’ – ‘For the greater glory of God’). Mr Williams was a longstanding church warden and the pillar was originally donated by a Mr N.T. Richards. Coupled with the now mounted cross, the monument was dedicated by the Reverend John Pearce.

The Oliver And Other Memorials

There are many memorials to local and influential families and clergy on the internal walls as well as in the surrounding churchyard, family vaults and fine examples of 15th century stained glass.

Many of the memorials date back to the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries and more recently and all bear witness to the fascinating lives led by those commemorated.

One such which has drawn attention is the pillar memorial in the churchyard dedicated to John Oliver of nearby Trevarno, erected during 1741 by his son, Doctor William Oliver (b.1695 d.1764), inventor of Bath Oliver biscuits which are a dry biscuit or cracker normally consumed with cheese. Designed by the noted antiquarian, geologist and clergyman, Reverend William Borlase (b.1696 d.1772) a friend and associate of Doctor Oliver, the memorial carries an epitaph by the poet Alexander Pope (b.1688 d.1744) an acquaintance of both.

A centre of Cornish wrestling tournaments in the past and home to many wrestling champions of the past, Sithney and its parish church are worthy of a visit. The church is now a Grade 1 Listed Building and continues as a place of worship with services occurring on a regular basis. The church is often open for public access.

References

- Placenames in Cornwall and Scilly – Craig Weatherhill, Wessex Books in association with Westcountry Books, Launceston, Cornwall 2005

- The Cornish Church Guide and Parochial History of Cornwall – Charles Henderson, D.Bradford Barton 1964

- Norman Architecture In Cornwall – A Handbook To Old Cornish Ecclesiastical Architecture – Edmund H. Sedding FRIBA, Ward and Co. B.T. Batsford and Co. London and J. Pollard, Truro, 1909 https://archive.org/details/normanarchitectu00sedd/page/n5/mode/2up

- The Buildings of England: Cornwall – Nikolaus Pevsner, Yale University Press, Newhaven and London, 1951 et al. https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780300095890/mode/2up

- The Parish Church of St. Sithney – Alan Todd, St. Sithney Parish Church, 1995

All images author’s own, except where stated.

See similar articles by Myghal Map Serpren

The recently issued January/February 2024 edition of the Cornwall Heritage Trust’s newsletter contained the news that the Trust has now assumed the management of the Duloe Stone Circle on behalf of the Duchy of Cornwall.

The Duchy owns numerous historic and ancient sites and some, notably the profit-making castles, have been placed under the less than satisfactory management of English Heritage.

However, it is encouraging that an increasing number of sites are now owned or under the faultless and careful management of the Cornwall Heritage Trust whose annual acquisitions have now raised the total number of sites the body administers to 16 following an impressive five gained in the past 18 months.

Those 16 monuments in the care of the Trust represent a wide span of historic periods from the Prehistoric, through the Mediaeval era and into Victorian industrial times.

Duloe is a village between Liskeard and Looe in Cornwall and just to the South of the settlement, a small oval stone circle is located, comprising eight white quartz monoliths of which seven continue to stand.

The circle has a varying diameter measuring just over 38 feet by 33 feet 6 inches thus making it the smallest of Cornwall’s circles.

The circle dates from the Bronze Age (2500BCE to 801BCE) and the use of white quartz for all the stones makes it unique amongst stone circles in Cornwall.

The stones are of various heights ranging from three feet three inches to seven feet ten inches and the four largest stones which stand at the cardinal points of the compass have been estimated to weigh up to nine tons each.

A field hedge bisected the circle until 1858 when it was removed and in 1863, three of the stones were re-erected during which a Bronze Age urn containing cremated human bones was recovered.

This find resulted in the Cornish antiquarian William Copeland Borlase FSA (b.1848 d.1899) suggesting in his ‘Nænia Cornubiæ’ published in 1872 that the circle originally retained a low barrow and thereafter the site became known as ‘The Druids Circle’.

However, the late Cornish historian and archaeologist Craig Weatherhill (b.1950 d.2020) thought the stone circle appeared too large to have retained such a barrow.

With tourism, housing and roadbuilding development virtually out of control in Cornwall resulting in damage and even loss of some ancient sites, and with Duloe having been at risk from tourism-related development as noted in the Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Heritage Environment Record, its management by the Cornwall Heritage Trust cannot have come too soon.

This is not the first instance of the Trust having saved historic sites and coupled with its impressive public and educational schools outreach programme, increasing membership and popular campaigns, it continues to grow in stature in Cornwall, and is far more principled than other heritage bodies which place profit and the ‘Disneyfication’ of Cornwall’s unique heritage over and above care for the monuments.

A link to the Cornwall Heritage Trust website can be found here: https://www.cornwallheritagetrust.org

Reference:

- Cornovia: Ancient Sites Of Cornwall & Scilly – Craig Weatherhill, Halsgrove, 2011

Image:

- Duloe Stone Circle – Philip Halling – Creative Commons – geograph.org.uk

In what is becoming far too frequent an event, another ancient monument has been damaged in Cornwall due to the carelessness of a driver.

The Trevellan or Trevellion wheelheaded cross is one three ancient crosses located in Luxulyan parish, in the village of Lockengate. The cross has previous damage, possibly due to its earlier movements. First recorded in 1870 at Trevellion Farm in use as a hedging stone, it was moved to the Mission Chapel in 1902. When the chapel was sold in 1972, the cross was placed in its current location at the roadside at Lockengate.

This wheelhead cross is rough-hewn and has similar cross designs on both faces. It was mounted on a modern base and stood nearly 2m high.

But the cross has now been dislocated from its base due to a vehicle reversing into it, judging from tyre tracks in the following photo, supplied by Cornwall Crosses expert Andrew Langdon, to whom we are indebted:

Luckily, the cross shaft does not appear to have been fractured, so it should be able to be re-set without too many problems.

Questions remain though: was this just carelessness, or a deliberate act? And why do so many of our ancient monuments get damaged by vehicles every year? It’s not just our wayside crosses (Cornwall is blessed with several hundred such monuments) but also our ancient bridges and other scheduled buildings. It is a fact that many Cornish roads and lanes are narrow, and modern vehicles are larger than at any other time. But the A391, on which this monument stands, is not a minor lane but a fairly busy road, leading from the A30 to St Austell. The cross is not close to the roadside, but set back, on a junction:

There is therefore no obvious reason why a vehicle would need to use the grass verge in a reversing manoeuvre. So was it hit head-on, by a driver who possibly lost control trying to turn left too late or too fast? Unlikely but possible…

Negotiations are underway to have the cross re-erected and we can only plead with all drivers: Please take care and treat our ancient monuments with the respect they deserve. Most all of them pre-date the motor vehicle age and should be allowed to delight and educate future generations to come.

By Myghal Map Serpren

Nance

Nance Farm is found in Illogan near Redruth in Cornwall. The valley which the farmland overlooks is wooded, and at its base, the B3300 road leading from Redruth enters the seaside village of Portreath with its former industrial port and harbour.

Nance derives from the Cornish word ‘nans’ meaning ‘valley’ and the word is in use in many other placenames throughout Cornwall as well as being a family name.

Situated on a high spur of land at the farm and overlooking the valley below as well as the valley which joins it from Illogan, an earthen round stands guard and is thought to date from the Iron Age period, 800BCE to 42CE.

As is common across Cornwall, most fields are named, and during the 18th and 19th centuries the one in which the round stands was called ‘Goon an geare’ which translates from Cornish as ‘downland of the fort’. This later became ‘Gullen Gear’, thence ‘Golden Gear’.

Nance round or hill fort comprises an oval part bivallate structure with the greater diameter being around 380 feet and the lesser 341 feet.

The surrounding ramparts are between around six feet and six feet seven inches in height and the ditches, of which there originally appear to have been two, currently measure around two feet four inches in depth. The double ditch remains on the southwest side of the round.

The entire round occupies an area of around two acres.

An additional rectangular enclosure appears to have existed as an appendage on the southeast side of the round, a fairly rare feature.

The ’round’ is complete except where a section of the outer bank and ditch on the North to North East side has been removed.

No obvious entrance to the round has ever been identified.

Prehistoric (500,000BCE to 42CE) flint scrapers have been found on site.

A matter of a few feet to the West of the enclosure there are traces of an oval ring ditch earthwork measuring some 78 feet 9 inches by 59 feet. Nothing is visible at ground level but this has featured on aerial photographs.

Current analysis informs that it was probably a Bronze Age (2500BCE to 801 BCE) round barrow which has been ploughed down over the years.

Nance round has been used as part of the ceremonies observed by Gorsedh Kernow and indeed, the late Craig Weatherhill (b.1951 d.2020), noted Cornish historian, archaeologist, toponymist and author was Barded there in 1981 for his services to Cornwall.

There have been suggestions from many sources that Nance round and hillfort served as a trading post. This is entirely possible bearing in mind its close proximity to the cove below and the sea is known to have washed further inland into the valley than it presently does.

A local tale informs that the earthwork is of Roman origin and was the site of a great battle in the distant past. However, it predates the arrival of any Roman influence although a battle may have occurred there as others are recorded along the local stretch of coast and adjacent moorlands.

The round is situated on farmland and access is best requested from the landowner.

Nancekuke

Of interest is the fact that immediately across the deep valley below Nance which now carries vehicular traffic from further inland along the B3300 to Portreath, a sister earthwork is recorded at Nancekuke.

Nancekuke which was recorded in 1170 as ‘Nanscoig’ is a Cornish placename deriving from ‘nans cog’ meaning ’empty valley’.

This earthwork was also a round dating from a similar period to the one at Nance and was written of by renowned antiquarian and historian Charles Henderson (b.1900 d.1933) who at a very young age visited the site during 1916 noting:

“On the other side of the valley (from Nance) is the hamlet of Great Nance-kuke, and between it and the cliffs, a distance of about a half mile, are the scanty remains of a small earthwork. It stands in a field and has been greatly ploughed down, though its outline can still be traced. The interior was raised artificially to make a level space and hence, though the enclosing rampart has been quite ploughed away, a terrace still marks its site. This terrace is still further emphasized by a shallow depression around it—all that is left of the encircling fosse. As will be seen on the plan, a hedge intersects the camp on the west side, and the shape is oval, 65 yards by 45 yards, not circular. At ‘A’ (referring to his sketch, see above) the terrace is quite 5 ft. in height.”

The Royal Air Force assumed control of the larger part of Nancekuke at the commencement of the Second World War and by 1941, the airfield constructed there became RAF Portreath, a Fighter Command station. The building of runways and other structures wiped away many ancient sites and although the site is no longer an active airfield, a chemical warfare establishment was on the former air station from the early 1950s through to the end of the 1970s and tons of toxic nerve agents produced and stockpiled there causing widespread environmental damage and death to employees. The area remains in use as an air defence radar station with upgrades being carried out as recently as 2020. Limited public access does occur for specific events.

Before the destruction inflicted to clear the area had occurred, field placenames which were recorded during the 18th century give a clear indication of the existence of a sister to the round and fort at Nance just opposite.

One such field had the name ‘Geer’ deriving from the Cornish ‘ker’ or ‘cayr’ meaning ‘fort’ and another ‘Todden Kere Common’ from the Cornish ‘todn ker’ translating as ‘grassland of, or by the fort’.

The site of the round at Nancekuke was visited by an Ordnance Survey fieldworker during 1970 and he recorded a slight oval feature measuring approximately 164 feet by 197 feet.

Nearby several implements dating from the Mesolithic (8000BCE to 4000BCE) and Neolithic (4000BCE to 2500BCE) periods were recovered during archaeological excavations carried out during 1940 by Charles Kenneth Croft Andrew (b.1899 d.1981). Amongst other artefacts, these items comprised arrowheads, scrapers, blades and borers and a cup marked stone.

A nearby barrow of which there are no remains probably due to wartime construction work, was also examined by Andrew resulting in him recording the presence of a grave pit, a fire site and a charcoal patch. Pottery thought to date from the Bronze Age (2500BCE to 800BCE) as well as a holed and a cupped stone were found together with the remains of an oak Cornish shovel at the base of a ditch surrounding the barrow site which measured some 56 feet in diameter.

References

- Placenames in Cornwall and Scilly – Craig Weatherhill, Wessex Books in association with Westcountry Books, Launceston, Cornwall 2005

- Cornovia – Ancient Sites of Cornwall and Scilly – Craig Weatherhill, Halsgrove, Somerset, 2009

- Cornish Archaeology – Hendhyscans Kernow Number 10 – Journal of the Cornish Archaeological Society, 1971

All images obtained as stated.

See similar articles by Myghal Map Serpren

We conclude Myghal Map Serpren’s look at Camborne Church by focussing on the Churchyard Crosses.

The Connor Downs Cross ‘Maen Cadoar’

The Connor Downs Cross perhaps better known as ‘Maen Cador’ is found in the churchyard to the West of the tower.

Also known as ‘Meane Cadoarth’, ‘Meane Cadoacor’ and ‘Maen Cadoar’, with ‘Maen’ deriving from the Cornish ‘men’ meaning ‘stone’ and with the descriptor being a personal name, this long stone is believed to date from the Bronze Age (2500BC to 801BC) but was subject to extensive alterations to convert it into a Christian cross in the Early Mediaeval to Mediaeval period.

It was initially situated on the boundary of the Gwithian and Gwinear Parishes at Connor Downs and recorded in the Gwinear parish records of 1613 as “Maen Cadoarth” and “the Battle Stone” and in 1651 as “the long stone called Meane Cadoarth”. By 1755 it was said to be laying at a roadside between Camborne and Redruth and by 1896 it had become a gate post. Finally, the landowner of the Rosewarne Estate, Mr. Van Grutten, allowed the stone to be moved to its current position in 1907.

Measuring six feet ten inches in height with the width of the head being approximately 11 inches, the width of the shaft at the top is eight and half inches which reduces to one foot ten inches, alteration to the head of the former menhir made during the Medieval period (1066 to 1539) resulted in a cross formed by four rounded triangular sinkings. The shaft of the stone is beaded and the decoration consists of a panel with lines of shallow holes.

Local tradition now recorded informs that each hole represents the life of a man killed at the great battle at Reskajeage Downs.

Nothing is currently known of this battle. Some have speculated that the Cadoc included in toponymical research of Reskajeage is in the Cornish Royal lineage of King Doniert and that the spur and battle were named for him. Cadoc, also known as Condor, Candorus and other names, was a legendary Cornish nobleman and 16th Century antiquarians recorded him as being Earl of Cornwall during the Norman conquest.

Reskajeage itself was recorded as Roscadaek in 1317, Reskaseak Downs in 1673, Riskejeake Downs in 1723 and finally Reskajeage Downs in 1888, the name translates from the Cornish ‘ros Cajek’ as ‘Cadoc’s hillspur’. The downs themselves are named after the settlement of Ruschedek recorded in 1235.

Perhaps one of the greatest mysteries of Maen Cadoar is the real possibility that it commemorated a great battle which occurred back in the mists of time.

The Crane, Fenton-Ia or Saint Ia’s Cross

A Mediaeval (1066 to 1539) wayside cross known variously as the Crane Cross, Fenton-Ia and Saint Ia’s Cross stands in the churchyard just over 30 feet southwest of the church building.

It was recorded as being in the grounds of the now vanished Saint Ia’s Chapel at Reens in the nearby Troon during 1750 by that great antiquarian, geologist and naturalist the Reverend William Borlase (b.1696 d.1772).

By 1896, it was recorded as being at Crane on the outskirts of Camborne where it was employed as a support for a well’s winding mechanism and five holes had been drilled into the cross shaft and remain to this day as evidence of its misuse.

It was subsequently recovered to Saint Martin and Saint Meriadoc’s Church where it remains.

Standing to a height of some six feet one inch with the head measuring around one foot six inches in diameter and nine inches in thickness, this granite cross is marked with an equal limbed cross with expanding limbs extending towards a beaded edge.

The monument is quite worn but on one side of the cross shaft which now faces East there is decoration consisting of vertical lines and triangles which is barely visible.

It has been cemented onto a rectangular cross base, also of granite and a cement repair has been conducted near the base of the shaft.

With a slate plaque bearing the words “This ancient Cornish cross was found at Crane, Camborne”, this cross base is worthy of note in its own right.

An iron link remains on the base and the parish stocks were once attached to this.

Current thinking has it that the base was probably part of an original churchyard cross now known as the ‘Chancel Wall Cross’ which is mounted on the external East wall of the church building.

The ‘second’ Crane Cross

The so-called ‘Second Crane Cross’ has now been built into the church wall just inside the South door.

Having also been repurposed during a later period as part of the well workings at Crane as had occurred with the Crane or Saint Ia’s Cross, this small cross slab was discovered under the Saint Ia’s Cross during 1896 by Joseph Holman.

It is thought that this cross slab was carved to place on the wall of the now long lost chapel which stood at Crane and was never designed to be a freestanding wayside cross.

According to the local historian and author Thurstan Collins Peter (b.1854 d.1917) who saw the cross before it was mounted in its current position, the reverse face appeared unfinished possibly due to a flaw in the granite.

A broad limbed Latin cross is visible on its exposed side and the bottom of this ends with a square step.

Brought to the relative safety of the churchyard shortly after its discovery, it was subsequently taken into the church itself and later fixed to the wall inside the South door where it remains.

The Chancel Wall Cross

The final cross to be discussed is known as the ‘Chancel Wall Cross’ for it has been built into the exterior of the Eastern wall of the South Aisle of the church below the window.

This cross is of granite and in what has become known as the Greek style with limbs which expand toward the circumference of the head.

Measuring one foot seven inches in height by one foot seven and half inches in width, a reference to it by the then Curate of the neighbouring All Saints Church at Tuckingmill and a keen antiquarian, the Reverend Arthur Adams, the cross was recut before being mounted which explains its excellent condition.

The Cornish archaeological artist John Thomas Blight FSA (b.1835 d.1911) made note of this cross during 1860 and sketched it.

By 1878, work on the South Aisle of Camborne Church was completed and the cross was built into the external wall where it remains to this day.

As previously noted, it is more than likely that the original base for this cross is now used in the Crane Cross.

Summary

As will be gathered, there is much of great historical interest at Saint Martin and Saint Meriadoc’s Church in Camborne, far more indeed than could ever be written in a precis such as this.

The building and many of the monuments about it are listed and scheduled but this church is primarily a place of worship and a community hall to the rear is used for many different events.

Of note is that part of the interior is undergoing renovation and the original stonework is being exposed which may contain yet more secrets. A brief examination revealed a stone with chevron markings during our visit.

In addition to Sunday services, the church is open to visitors on Tuesdays from 2pm to 4pm and Saturdays from 10am to 12 noon although it is strongly advised that before any visit is made, the necessary enquiries are carried out with the church.

Grateful thanks go to the Church Warden and lay preacher Mr David Fieldsend and to Mrs. Fieldsend for being such charming and accommodating hosts during the visit to this magnificent church.

References

- Placenames in Cornwall and Scilly – Craig Weatherhill, Wessex Books in association with Westcountry Books, Launceston, Cornwall 2005

- A Guide to Cornish Place-Names – R. Morton Nance, The Federation of Old Cornwall Societies, 1950

- Cornish Church Guide And Parochial History Of Cornwall – Charles Henderson M.A., D. Bradford Barton Ltd., Truro, 1964

- Stone Crosses in West Cornwall (including The Lizard) – Andrew Langdon, Federation of Old Cornwall Societies, 1999

- Ancient and High Crosses of Cornwall – Ann Preston-Jones, Andrew Langdon, Elisabeth Okasha, University of Exeter Press, 2021

- Early Cornish Sculpture – Ann Preston-Jones, Elisabeth Okasha and Others, British Academy, 2013

- Cornish Crosses, Christian and Pagan – T.F.G. Dexter BA BSc PhD, Henry Dexter, Longmans Green and Co., 1938

- Old Cornish Crosses – Arthur G. Langdon, John Romilly Allen, Joseph Pollard Pub. of Truro, Cornwall 1896 (available on the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/oldcornishcrosse00lang/mode/2up)

All images author’s own, except where stated.

See similar articles by Myghal Map Serpren

We continue our visit to Camborne Church, with Myghal Map Serpren.

The ‘Leuiut Slab’

This remarkable inscribed altar stone slab which has become known as the ‘Leuiut Altar Slab’ is situated just forward of the screen on the South aisle of 1879 and into the Lady Chapel which was extensively renovated and restored in 1989.

Known as the ‘Pendarves Aisle’ after the influential and wealthy landowners of the period, the Pendarves family vault lays beneath the floor here.

Dated as being from the 10th century by the late Professor Antony Charles Thomas CBE DL FBA FSA FSA Scot (b.1928 d.2016), a local tradition has it that the slab originated from the now-lost chapel of Saint Ia near Troon, less than two miles distant. This has now been accepted as an accurate account of its origins.

Constructed of red granite, the slab is inscribed with the words ‘’LEUIUT IUSIT HEC ALTARE PRO ANIMA SUA’ which translates as ‘Leuiut ordered this altar for the sake of his soul’.

Also found on the Leuiut Slab are five Consecration Crosses which are believed to have been engraved on it as part of a reconsecration which occurred during the later Norman times.

The Leuiut Slab lay in the churchyard for many years before being stored under the church’s Communion Table. It was placed in its current position as part of a First World War memorial scheme.

The slab is mounted on a slate pillar and is designed to closely resemble a similar altar in the village of Venasque in the Vaucluse department of Provence, France.

The Leuiut Altar has frequently been described as Saint Martin and Saint Meriadoc Church’s greatest single treasure.

The wooden cross placed on the slab was constructed of oak recovered from part of the 15th-century aisle roof above.

There is a macabre local tale regarding the Lady Chapel and the Pendarves Vault beneath it. This informs that The Honourable Sir William Pendarves (b.1689 d.1726) who was interred earlier had a coffin of copper constructed from the first of that metal brought up from his mine at the nearby South Roskear and was even known to drink punch from it at Pendarves House. During 1780, the vault and coffin were opened to inter the remains of another member of the family and those carrying out the work were confronted by the body of Sir William with hair and nails which had grown considerably.

The Mermaid and the Green Man

The Parish Church of Saint Senara in Zennor, Cornwall has been frequently visited and written of, owing to the legend of the ‘Mermaid of Zennor’ whose image is to be found on the 600-year-old ‘Mermaids Chair’. It is not generally realised that a mermaid exists in Saint Martin and Saint Meriadocs’s as well.

An examination of the Sanctuary at the head of the Chancel reveals walls panelled with former 15th-century bench ends which have a range of creatures carved on them including a mermaid.

Other carvings include a Green Man, a pagan Celtic fertility symbol usually depicted with foliage growing from them or around them. These are found in a large number of churches and cathedrals but often need to be sought out.

The Sedilia, the bench designed for the priest, is similarly constructed of former bench ends dating from the 15th century.

The Oddfellows and other stained glass windows

Saint Martin and Saint Meriadoc’s has no less than 15 beautiful stained glass windows.

Five in the North Aisle commemorate individual families and date from the 1960s and depict ‘The Holy Family with the Arms of the Diocese of Truro and Saint Martin’, ‘The Marriage at Cana, Christ and the Children’, ‘The Triumphal Entry into Jerusalem’ and ‘Christ in Majesty’.

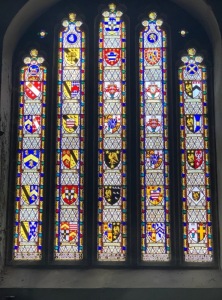

The East window of the Lady Chapel, continues the chapel’s close connection with the Pendarves family by having a magnificent collection of 29 heraldic shields which relate to the genealogy of the family. The window is dedicated to the memory of Edward William Wynne Pendarves (b.1775 d.1853) and dates from 1864.

The East window of the outer South Aisle depicting ‘The Works of Mercy’ commemorates the Reverend Canon William Pester Chappel M.A. (also Chappell, Chapple etc) (b.Truro 1828 d.Camborne 1900) dates from 1898 and marked his 40th year as Rector of Camborne which commenced in 1858 and finally ended with his death.

Reverend Canon Chappel was indeed a popular clergyman for another stained glass window situated in the outer South Aisle depicting ‘Saint Peter, Saint Andrew and Saint James’ was dedicated to his memory during the year of his death, 1900.

The outer South Aisle also has stained glass windows depicting ‘The Last Supper and the Institution of Holy Communion’ dating from 1969 and in memory of members of the Gundry family, ‘The Washing of the Disciples’ Feet’ in memory of members of the Pellew family, ‘The Commissioning of the Apostles’ in memory of a further Rector of Camborne from 1934 to 1944, The Reverend Canon D.E. Morton and his wife and ‘The Parable of the Vine and Branches’ dating from 1961 in memory of members of the Odgers family. Many of these are longstanding local families with modern descendants.

The inner South Aisle has a window showing ‘Christ and the Impotent Man at the Pool of Bethesda’ dating from 1864 and in memory of Edward Lanyon.

The Belfry window shows ‘Saint Martin dividing his cloak with the beggar and Saint Martin’s Baptism’ and dates from 1862 having been funded by the younger men of the parish.

Of great personal interest is the West window in the North Aisle, ‘The Oddfellows’ Window’.

This was paid for by the Loyal Basset Lodge of the Oddfellows Friendly Society and consecrated by the Reverend Canon Chappel in 1863. It celebrates the marriage of the then Prince of Wales, Albert Edward, later King Edward VII (b.1841 d.1910), to Princess Alexandra of Denmark, later Queen Alexandra (b.1844 d.1925) which occurred on 10th March, 1863 at Saint George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle.

The four-light window was paid for by the Lodge bearing the family’s name at the then substantial cost of nine shillings and sixpence (47.5 decimal pence) per foot of glass, around £50 per foot in today’s prices.

Bearing the dedication “Presented by the Odd Fellows of the Loyal Basset Lodge AD MDCCCLXIII” the first light depicts the Dove of the Holy Spirit, the second light the emblems and symbols of the Odd Fellows with the All Seeing Eye with the emblem of the Society beneath flanked by the maternal figure of Charity with children to the left and the female figure of Hope with her anchor to the right, the third light a widow and her children pursued by Want who approaches from over the late husband’s grave and the words “Widows’ & Orphans’ Fund over a figure representing succour and protection, with the fourth light depicting Agnus Dei, the Lamb of God, a symbol of Jesus Christ.

These 15 windows are truly magnificent and worthy of close inspection.

Next time, we’ll look at the crosses in and around the churchyard.

References

- Placenames in Cornwall and Scilly – Craig Weatherhill, Wessex Books in association with Westcountry Books, Launceston, Cornwall 2005

- A Guide to Cornish Place-Names – R. Morton Nance, The Federation of Old Cornwall Societies, 1950

- Cornish Church Guide And Parochial History Of Cornwall – Charles Henderson M.A., D. Bradford Barton Ltd., Truro, 1964

All images author’s own, except where stated.

See similar articles by Myghal Map Serpren

By Myghal Map Serpren

Introduction and toponymy

Camborne is situated in the former Hundred of Penwith in West Cornwall.

The Cornish language was the main tongue of the area until the early 18th century and so it follows that the name of the town is derived from the Cornish placename ‘Cambron’ which it was known as from c.1100 to c.1700. This translates from the Cornish ‘cam-bron’ into English as ‘crooked hill’.

Now very much a post-industrial settlement, it is perhaps difficult to believe that Camborne was once one of the most wealthy tin mining towns in the world, and home to the internationally recognised Camborne School of Mines and hard rock machinery production company, Holman Brothers.

The Saint Martin and Saint Meriadoc’s Parish Church of Camborne

Camborne has a fine Parish Church dedicated to two Saints, the Celtic Saint Meriadoc (Meriasek in Cornish, Meriadocus in Latin) and St Martin. Thought to have lived around the 7th century and to have been Bishop of Vannes, Meriadoc is commemorated in Brittany, where both his bell and holy well are preserved and situated in Stival, a small village near Morbihan.

An account of the life of Saint Meriadoc is contained in the Cornish language play ‘Beunans Meriasek’ (Cornish: ‘Life of Meriasek’) dating from 1504, which was rediscovered in Wales in 1869.

This tells of the Saint arriving in Camborne and founding a church beside the pre-existing chapel of Saint Mary.

During the 15th century, Saint Meriadoc’s patronage was shared with Saint Martin, Bishop of Tours in France (d. 397), a popular Mediaeval Saint.

During the Mediaeval era, both Meriadoc and Martin were recognised in Camborne, however, it was not until as relatively recently as 1958, following many years the Church became officially known as the ‘Church of Saint Martin and Saint Meriadoc’.

A Chapel of Saint Mary is recorded on the site in 1435 and 1445 and until 1671, two churches were contained within the surrounding walls, the parish church and a chapel and shrine dedicated to the Virgin Mother.

The Reformation saw the demise of the chapel and shrine which although renovated during the 1630’s, entered a period of terminal decline during the times of Oliver Cromwell (b.1599 d.1658) in the period 1653 to 1658. The building was then used as a source of stone to allow for the construction of a nearby poor house.

The structure of the current church dates mainly from the later 15th century although it does incorporate some fabric of earlier structures and has artefacts and monuments set in and about it from considerably earlier still. It has been suggested that the site was in use well before the Norman period. Sections of the wall enclosing the surrounding churchyard date from Mediaeval times.

Initial restoration of the church occurred during 1861 and 1862 followed by further considerable restoration and enlargement work during 1878 and 1879 under the supervision of the renowned church architect James Piers St Aubyn (b.1815 d.1895).

In addition to the existing 60-foot high, three-stage West tower which has eight bells, the nave and chancel and the North and South aisles, an addition to the South aisle was constructed together with a magnificent four-span roof.

Completion of this work allowed for an increase in the seated congregation from the earlier 488 to a remarkable 668 people.

There is much of interest both within and without the large church building, which we shall cover in Part 2 later this week.

References

- Placenames in Cornwall and Scilly – Craig Weatherhill, Wessex Books in association with Westcountry Books, Launceston, Cornwall 2005

- A Guide to Cornish Place-Names – R. Morton Nance, The Federation of Old Cornwall Societies, 1950

- Cornish Church Guide And Parochial History Of Cornwall – Charles Henderson M.A., D. Bradford Barton Ltd., Truro, 1964

All images author’s own, except where stated.

See similar articles by Myghal Map Serpren

You must be logged in to post a comment.