You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Ancient trackways’ category.

An opinion piece from someone whose family heritage in the area extends back hundreds of generations:

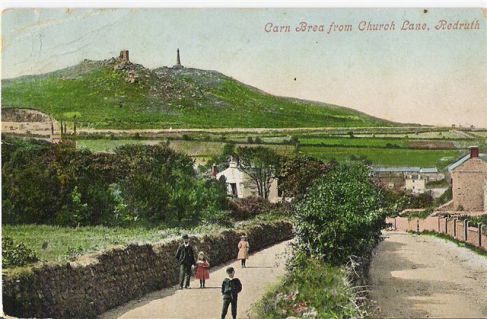

Carn Brea, between Camborne and Redruth in Cornwall, is an enormous hilltop site of historic significance.

With evidence of human habitation extending back over 5,000 years, this tor enclosure comprising extensive ramparts and a ditch and traces of 14 Neolithic longhouses, many pottery and flint artefacts including no less than 700 arrowheads have been discovered on this ancient hill.

Gold Gallo-Belgic coins in circulation over 2,000 years ago have been found on Carn Brea.

Home to an early Mediaeval Chapel thought to be dedicated to Saint Michael and later fashioned into a small castle and hunting lodge as well as a 90-foot-high Celtic Cross erected as a monument to Francis Bassett, 1st Baron de Dunstanville and Bassett, the hill is a local landmark and generations have spent leisure time exploring it and its mysterious wells and granite rock formations.

Views of the local area from its upper parts, around 630 feet above sea level, are spectacular with a vista extending down to the Celtic Sea and Atlantic Ocean.

Carn Brea has been an inspiration to many writers and poets through the centuries. It is a place of myth and legend.

Cornwall is facing unparalleled destruction of its natural and human history which is overtaking the excesses of the tin and copper mining industrial boom of the 19th century.

Astonishing levels of house building, road widening and construction have seen the loss of archaeological sites of great antiquity and left farmers in tears at the loss of land through compulsory purchase that their families worked for generations, coastal development and so-called luxury modern mansions and holiday resorts accompanied by a vast increase in population has resulted in much being swept aside in the name of progress.

Environmental groups are increasingly expressing concern over the loss of fauna and natural habitats. Our seas suffer from alarming levels of human pollution rendering many unsafe to bathe in.

How sad it is to see a place of such huge historical and natural importance as Carn Brea, a place which has served as a refuge from the destruction, become nothing more than a dumping ground for fast food packaging, fly-tipping and even supermarket trolleys which have been pushed along lengthy trackways and abandoned on this extraordinary hill.

My ancestors must surely be spinning in their graves!

by David McGlade, Chairman and Trustee

The Offa’s Dyke Association (ODA) turns 50 in 2019. A membership-based charity the ODA operates a visitor centre complete with interpretive displays, tea room and a library, named after Frank Noble, the ODA’s founder. It also publishes a full colour newsletter three times year, an annual accommodation guide to the National Trail, organises talks and walks and will soon have a new website rebuilt entirely from scratch.

The classic view of Offa’s Dyke, curving across Llanfair Hill, South Shropshire © jimsaunders.co.uk.

In 2016 the ODA launched its own Conservation Fund with the simple aim of financially assisting maintenance works and projects that promote the long-term conservation of Offa’s Dyke, other scheduled and non-scheduled archaeological features along the line of the National Trail, also areas with a nature conservation interest. Anyone, for example, a farmer or a local authority, can apply to the fund as long as the proposed works have a long-term conservation aim and are deliverable. The first grant was awarded to Shropshire Council towards the cost of a small drainage scheme in the Shropshire Hills AONB designed to reduce walker and livestock pressure. The ODA has since agreed in principle to provide a matching funding contribution for a conservation scheme designed by the National Trail Officer for works to the Dyke and Trail in the Wye Valley near to the Devil’s Pulpit.

.

Shropshire County Council conservation works to the Dyke and National Trail at a site called ‘Scotland’ in the Shropshire Hills AONB to rectify a drainage issue. (Photo copyright Andrew Lipa, Shropshire County Council.

The ODA sees the Conservation Fund as being crucial to its own future survival. It meets perfectly its charitable aim and establishes a direct link between an individual membership subscription and the wellbeing of the monument. Trail walkers, other visitors and locals alike will hopefully see this as a tangible benefit of joining the ODA. The fund’s most significant involvement to date is an on-going collaboration with Cadw and Historic England towards a strategic conservation management plan approach for the full length of the Dyke. As an equal partner in this project the ODA’s status as a serious conservation focused organisation in both countries is firmly established.

Not everything in the past two years, however, has been plain sailing for the ODA. The writing had been on the wall for some time but 12 months ago the Association was hit with the news that its long-standing contract with Powys County Council to provide tourism information functions at the Offa’s Dyke Centre would cease at the end of 2016. The financial realities of the day meant that the Offa’s Dyke Centre, together with all of Powys’ other community supported Tourism Information Centres, would lose their funding. This only speeded up the root and branch review of every activity undertaken by both the charity and within the Offa’s Dyke Centre with the aim of making good the loss of direct funding support. The tea room, library/second meeting room, improved newsletter, plans for the website, improved financial and management systems, and the conservation fund, are facets of a strategy that is starting to pay off.

The ODA hopes to broaden its appeal and give potential members more reasons to join the Association, pay a visit to the Centre to view the interpretive display, buy a souvenir or a coffee and cake, browse the library, (it has an unrivalled collection of books on the Dyke and Welsh Marches), hire a meeting room or perhaps make a donation. Offers of help at the Offa’s Dyke Centre are always welcome. We are likewise always on the lookout for contributors willing to write original content for the newsletter and website and also currently need people with skills in marketing, fundraising, as well as website management. The ODA is now financially on its own but it will strive to both maintain its existing functions at the ODC as well as be innovative and start conversations with anyone willing to collaborate.

The Association’s AGM is always a highlight of the year and 2017 is no exception. The guest speaker is Pieta Greaves, Staffordshire Hoard Conservation Coordinator for Birmingham Museums Trust who is talking about ‘The Conservation and Research of the Staffordshire Hoard’. (Talk at 4pm, 29th April 2017. Free to ODA members, £3 to non-members).

For membership information, opening hours, room hire, library, conservation fund, tickets to AGM talk: contact the Offa’s Dyke Centre on 01547 528753. Email: oda@offasdyke.org.uk Website: www.offasdyke.org.uk

It has been some time since we started our journey down the Neolithic M1. You may recall that we started at Holme-next-the-Sea in Norfolk, and travelled down the Peddars Way to Knettishall Heath near Thetford. We then continued on the Icknield Way through Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the borders of Hertfordshire at Royston.

So we pick up our journey again in the centre of Royston, by the glacial erratic that gives the town its name. The Royse Stone once held a cross erected by a Lady Roisia. Royston sits at the junction of the Icknield Way and Ermine Street, the latter being one of the most important Roman roads in the country, leading from London to York. Not far from the stone is the entrance to Royston Cave, an enigmatic opening carved into the solid chalk below, discovered in 1742 when a shaft covered by a millstone was uncovered. The cave walls are covered in medieval (and possibly earlier) carvings, and are well worth a visit!

A short distance west from the town is Therfield Heath which contains a barrow cemetery consisting of a long barrow, and several smaller round barrows.

The modern Icknield Way Trail diverts south here, following the high ground through the villages of Therfield, Sandon and Wallington toward Baldock. But north of the trail, there are several scattered tumuli, roughly following the course of the modern A505 road. This suggests that maybe the prehistoric way followed the lower ground at this point. The scant remains of a hillfort can be found at Arbury Banks, just outside Ashwell, one of 6 such hillforts spread along the northern Chilterns.

Reaching Baldock, the area contains a wealth of archaeology, including the sites of two known Neolithic henges at Weston and Norton.

Weston Henge

From Baldock, the Icknield Way continues west through Letchworth Garden City, crossing the River Hiz at Ickleford. The modern trail once again diverts from the old path and continues to Pirton, which has a motte and bailey construct. There is a current project, run by Reading University, to investigate whether certain mottes could have had earlier origins as Neolithic mounds, is the motte at Pirton a candidate, I wonder?

South-west of Pirton, the Knocking Knoll long barrow can be found. Although now damaged by ploughing activity, this was excavated by Ransom in 1856. Some 100 years later, in the mid-1950s farm labourers uncovered a chalk cist containing a crouched burial, which was presumed to have its origins in the ploughed E half of the barrow.

Rejoining the old path and continuing south-west past the Pegsdon Hills nature reserve, Ravensburgh Castle can be seen to the north. Finally, the trail passes the Galley Hill barrow cemetery before getting lost in the urban sprawl of Luton.

We’ll pause for a while once again here, and continue our journey anon.

This story, from County Westmeath, is worth publicising far and wide:

“In 2005, a 3,000 year old Bronze Age wooden road was uncovered in Mayne Bog in Coole, Co Westmeath. Described by An Taisce as “a major, timber-built road of European significance”, this was an archaeological find of huge importance. According to John Waddell, Emeritus Professor of Archaeology at NUI Galway, the Mayne road (or “Togher”) is, in terms of size, age, and antiquity “truly of European significance and on a par with those preserved in dedicated heritage centres like Wittemoor in Lower Saxony, Flag Fen in Peterborough (UK), and Corlea in County Longford”.

Mayne Bog is worked by Westland Horticulture, which extracts peat from the site. Despite carbon-dating the find to 1200 to 820 BC, the National Monuments Service – for some reason – did not issue a preservation order or record the road in the Register of Historic Monuments. Apart from two minor excavations, no serious archaeological work has been done on the discovery and – crucially – no legal impediment has been put in place to prevent the destruction of Mayne Togher. For the ten years since the find, Westland Horticulture has – entirely legally – continued to mulch something as old as Newgrange into compost for window boxes. At least 75% of the road is gone now. Dr Pat Wallace – former director of the National Museum of Ireland – has described this as “an international calamity”.

Not sure why your tomatoes won’t grow? Try Gro-Sure® Tomato Food from Westland Horticulture, which simply grows more.

{See also our previous article …. https://heritageaction.wordpress.com/2015/10/01/unique-opportunity-to-grow-your-plants-in-a-genuine-bronze-age-trackway/]

We continue our look at the ‘Neolithic M1‘, which stretches from Holme-next-the-Sea in Norfolk across country to Lyme Regis in Dorset.

Having followed the Peddars Way south from Holme-next-the-Sea down to Knettishall Heath near Thetford, we now pick up the Icknield Way.

..winding with the chalk hills through Suffolk, Cambridgeshire, Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire, Berkshire, and Wiltshire, it runs south-westwards from East Anglia and along the Chilterns to the Downs and Wessex; but the name is mysterious. For centuries it was supposed to be connected with the East Anglian kingdom of the Iceni: Guest confidently translated it as the warpath of the Iceni, and connected it with the names of places along its course, such as Icklingham, Ickleton, and Ickleford.

Excerpt From: Thomas, Edward, 1878-1917. “The Icknield Way.”

Today, the Icknield Way is part of the Greater Ridgeway long-distance path, but the actual extent of the original Icknield Way is open to debate. The acknowledged trail stretches from Knettishall Heath to Ivinghoe Beacon in Buckinghamshire, but stretches of the trail south of here are also marked on the O.S. map variously as the Chiltern Way, Ridgeway and Icknield Way. Indeed, there is an Icknield Farm just NW of Goring where the path appears to terminate.

Starting our journey from Knettishall Heath, on the heath itself a kilometre or so to the east is Hut Hill, upon which stands a well-preserved bowl barrow, which stands to a height of about 0.5m and covers a roughly circular area with a maximum diameter of 32m. Further east is a similar barrow in Brickkiln Covert, whilst just a couple of kilmetres to the West, and north of the Little Ouse river stand the Seven Hills tumuli at Rushford. These are oddly named as only 6 barrows remain in this cemetery area.

The trail heads west from here, before dropping south through the ‘King’s Forest’ to West Stow, where a reproduction Anglo Saxon village (and museum) is sited. We visited here in 2014. Another Seven Hills barrow cemetery is located a couple of kilometres west at Rymer though this one has not fared as well as the one at Rushford, with only faint traces of four barrows remaining.

From West Stow the trail crosses the River Lark and heads southwest, toward Newmarket, and skirting the town to the south. The modern long distance path deviates from a natural line here to follow the modern roads (and bypass the town) but in prehistoric times I have no doubt that a straighter track would have been the preferred route. Throughout this section, there are various early medieval earthworks; Black Ditch, Devil’s Dyke etc, all crossing the trail at approximately right-angles. It’s been suggested that these were territorial markers, demarking portions of the old route. There are very few prehistoric burial sites on this stretch of the trail, though there are several moated houses, many dating back to medieval times.

Continuing southwest, we cross the River Granta at Linton, and a short distance east are the enigmatic Bartlow Hills – an early Roman barrow cemetery quite unlike any other I’ve seen, in that the barrows seem disproportionately tall compared to their circumference. The highest of the hills is 15 metres tall, but these days the site is shrouded by trees and it is easy to miss them.

From Bartlow, the modern trail heads west toward Royston, departing somewhat from what would have been the original route, and crossing the River Cam at Great Chesterford, just south of Ickleton village and the Roman Road which is now the modern A11 road. We’ll halt at Royston for a while, and pick up the trail in the next installment.

In the first part of our look at the Greater Ridgeway, we examine the northern section of the route, known as Peddars Way, which runs from Holme-next-the-Sea on the coast, down to Knettishall Heath near Thetford.

The trail starts at Holme-next-the-Sea, but of course this small village has not always been situated on the coast, and may not have been the start or end of the trail as we know it today.

Holme-next-the-Sea is of course now famous as the home of ‘Seahenge‘ (Holme I) – an enigmatic timber structure exposed at low tide and controversially excavated/rescued by the Time Team in 1998. The preserved timbers can now be seen in a reconstruction of the monument in the museum at Kings Lynn, a few miles away. The timbers at Holme I came from a circle 21ft in diameter, comprising 55 closely-fitted oak posts, each originally up to 10ft in length. A second timber circle (Holme II) some 42ft in diameter was also identified 100 yards or so from the first. Timbers from both circles have been dated using dendrochronology, and were found to have been felled in 2049BC. Were these circles the focal point of the trail, or did it once extend even further in to what is now the North Sea?

From Holme, the trackway heads just east of south for approximately 20 miles. The modern track follows the course of a Roman Road, (does the Roman road follow the course of the original trackway?) though there is some debate as intermittent clues suggest a slightly different course for the earlier trackway to the west of the modern road. The village of Sedgeford is close to the line of the road, and is the site of a long running and on-going archaeological investigation which shows the area has been occupied since at least the Iron Age, if not longer. This is of course, Iceni country, and the village of Snettisham – where a fabulous gold torc (amongst other treasures) was discovered by metal detectorists – is also only a short distance further to the west.

Continuing southeast, we come to the barrow cemeteries at Bircham and Harpley Common, (where a strung-out line of barrows seems to suggest a slightly different route) and a couple of miles further to the east, Weasenham Lyngs – one of the largest barrow cemeteries in Norfolk, before arriving at Castle Acre. Castle Acre was the site of an important Norman Castle and Priory, both established after the Norman Conquest, which indicates the strategic importance of the route at that time.

The track continues south from here, passing to the east of Swaffham, roughly the half-way point of the Peddars Way. Until recently, there was a reconstructed Iceni Village tourist attraction at Cockley Cley to the west, but this has now been demolished, so ignore the signs if you see them! But the Bronze Age barrow cemeteries continue to pepper the line of the road at Little Cressingham, – where some gold torques were unearthed in a quarry in 1856 – Merton, and then Hockham Heath, passing a few miles to the east of the Grimes Graves flint mines before finally arriving at Knettishall Heath, where four modern long-distance footpaths meet: Angles Way, Icknield Way Path, Iceni Way and Peddars Way.

At this point, we’ll head west to pick up the Icknield Way, the subject of our next article. The Peddars Way shown on modern O.S. maps very much follows the modern long-distance path, but for a bit more authenticity, it’s possible to follow the ‘old’ path on the O.S. maps from the 1880s at the National Library of Scotland web site.

A major network of trackways, in use since Neolithic times runs from the Norfolk Coast near Kings Lynn, all the way across country to Lyme Regis on the Dorset coast, a total of some 363 miles.

Much of this trackway, known today as the Greater Ridgeway is still in evidence, and is incorporated into a series of modern long distance trails known by several names for its different sections:

- The Peddars Way – runs from Holme-next-the-Sea down to Knettishall Heath near Thetford in Norfolk.

- The Icknield Way – runs from Knettishall Heath, SE of Thetford across country to Ivinghoe Beacon in Buckinghamshire.

- The Ridgeway – runs from Ivinghoe Beacon to West Overton, west of Marlborough in Wiltshire.

- The Wessex Ridgeway – runs from West Overton, via Stonehenge, to Lyme Regis in Dorset.

It’s no coincidence that this set of trackways follows a geological band of chalk which runs diagonally across Southern England. Some of these trails overlap, as explained by the Friends of the Ridgeway website:

The Ridgeway, like other pre-historic routes, was never a single, designated road, but rather a complex of braided tracks, with subsidiary ways diverging and coming together. Successive ages made use of the route for their own purposes, and left the marks of their passage. Pre-historic barrows and burial mounds line the route and excavations have found implements and ornaments from many sources.

As the land lower down the slopes was cleared, a lower route became feasible in summer, closer to the spring line where water was accessible to travellers and their mounts. While The Ridgeway followed the top of the downs the Lower, or Icknield Way, runs parallel to it just above the foot of the slope, as far south as Wanborough near Swindon. To the north of the Chilterns, where the chalk is flatter, the routes come together. The Icknield Way was used and upgraded by the Romans for much of its length for both trade and military purposes.

In a series of forthcoming articles, we’ll be looking at each of these modern sections, noting some of the archaeological sites that sit on or near the trackways as we go.

(And no, I haven’t walked the whole route. Yet…)

Last Monday Amesbury Town Council said they were cancelling the event “due to problems with access to the planned starting point at Stonehenge, predicted traffic problems and rising costs.” Congratulations then to Councillor Fred Westmoreland and the Trustees on behalf of Amesbury Museum, for doggedly facing up to and overcoming a series of objections and obstacles.

The route has had to be changed but as Councillor Westmorland said: “It would be a different route and not involve Stonehenge but it is better than nothing. It would be cheap, cheerful and local. It is short notice but I’m sure that people would want to be part of it and it would be a shame not to have a lantern parade at all.” As big fans of the parade we totally agree. The precise nature of the “problems with access” at Stonehenge is unclear and it’s a real shame the Stones won’t be included this year but so far as we understand it EH are in favour of the parade in principle so the important thing is that there will be a parade, the tradition has been established, and hopefully it will include Stonehenge next year when the new access arrangements have bedded in.

It’s no secret why we are such fans of the parade. We think that public engagement with Stonehenge should involve a much wider spectrum of the public than at present. In addition, we think holding solstice celebrations in what may well be the authentic spot at the authentic time at minimal public cost is far preferable to holding them at the wrong spot at the wrong time at horrendous public cost. The fact that this year the former gathering will be absent and the latter one will be taking place is pretty hard to defend.

by Sandy Gerrard

In March last year 18 questions relating to the archaeological situation on Mynydd y Betws were asked. During May the answers provided by Cadw were published here. I also asked my local Assembly member (Mr Rhodri Glyn Thomas) to ask the Dyfed Archaeological Trust (DAT) the same questions and he kindly did this on my behalf. Having had no response in October I asked Carmarthenshire County Council for a copy of the DAT response and this was passed to both Mr Thomas and myself shortly afterwards. A commentary on the DAT response was then produced and sent to Carmarthenshire County Council. This series of articles present DAT’s responses in black and my own comments upon them in green. See part 1 of the series here.

GENERAL POINTS (continued)

In terms of the planning responses made by this Trust it is important to remember that the stone alignment, which is at the heart of Dr and Mrs Gerrard’s concerns, was not discovered until early January 2012. The original field work was carried out much earlier.

This recent discovery was only achieved because of mountain fires the previous summer and we are certain that the stone alignment, buried in tall heather and vegetation, would not have been discovered earlier if it had not been exposed by fire.

This issue is central to the whole debate. I believe that once planning permission had been granted the substantial area highlighted for destruction should have been looked at thoroughly and to do this vegetation that was going to be lost anyway should have either been cut or carefully burnt. This would have provided both archaeological and ecological benefits. The area could have been checked for “hidden” archaeology and the resultant fire-break could have represented the start of more positive management of the heather in the area. Instead no search was conducted of an area which was about to be destroyed and which both the Trust and Cadw had previously described as archaeologically important. Whether the stone alignment is prehistoric or not is not the main issue. The main issue is that no attempt was made to locate or record archaeological remains of ANY date in advance of a permitted development.

It is wholly wrong of Dr and Mrs Gerrard to criticise many other field archaeologists from a number of organisations for failing to make this discovery in the prevailing circumstances of dense vegetation cover. By January 2012 the stone alignment was very clear in a charred landscape and would have been easily observed by anyone walking in the area.

I am not aware that I have criticised anyone for failing to see the stone alignment in the “dense vegetation”. I have challenged the evidence for the hill being covered in dense vegetation as photographs taken at the time indicate a mosaic of different vegetation conditions. I have also asked on several occasions why a proper search was not conducted. My criticism is that nobody looked for or was asked to look for earthworks in these areas. Is dense vegetation seen as a valid excuse for not conducting a thorough search of areas about to be destroyed? Why is it wrong to criticise when such work was clearly not done? To do such work in future would mean more employment for fellow archaeologists and ensure such mistakes do NOT re-occur. If as fellow professionals it is wholly wrong to criticise how will understanding ever progress? Academically in ALL fields of research criticism of currently widely accepted views has shown they are often inaccurate. This comment is therefore blatantly insulting and shows scant regard for an understanding of how knowledge is obtained. Also to then add ‘anyone’ walking in the area would have spotted it after burning is clearly intended as a put down, but actually reinforces the main point I have been making from the start. If they had removed the vegetation obscuring the archaeology then indeed according to DAT it could have been spotted by “anyone”, but instead they choose to “sign off” the area without a proper examination simply because it happened to be covered in dense vegetation on the day allocated for the fieldwork. This is what is wholly wrong. Just because they didn’t bother to look for archaeology in the areas covered in dense vegetation, does not give them an excuse to treat with contempt those who did make the effort to have a look and honestly report their findings before it was too late. The fencing contractors and other operatives also failed to notice it, but of course anybody could….

____________________________________

For previous and subsequent articles put Mynydd Y Betws in our Search Box.

See also this website and Facebook Group

Whatever your views on building windfarms in sensitive locations, you’ll find this short video by Sandy Gerrard well worth viewing. There’s an unmistakeable and powerful symbolism to it. Welcome to the future!

.

You must be logged in to post a comment.